Don't motivate the highly motivated

Know when to diversify your approach, and why

It’s 10:30pm on a Friday, my coworker Andy (not his real name) just received a text from his boss.

Two weeks ago, you said X will be done today, is it done yet?

Andy has been working overtime everyday this past two weeks, working on a different project his manager prioritized two weeks ago.

Andy is a top-tier engineer, with great velocity, highly technical, and brilliant. His boss is a middle-manager, with unrelenting high standards, and always pushing his team to deliver more. Both are doing exactly what their bosses are expecting them to, but Andy was fuming and telling me he’s planning to quit his team. This is because the middle manager in this case is making two simple but critical mistakes.

Everything is not equally important

A manager who insists everything must be treated with highest priority but refuses to lay out relevant priority among competing tasks, is simply expecting to get more work done out of the same number of resources. This situation will simply wear down your team’s energy overtime and needs to be avoided at all costs.

Throughout my career I have seen this pitfall slow down people managers, and can be avoided with following four simple steps:

Have a plan in place, this can be your scrum board, your backlog, or your status wiki pages. Something which lays out your contracts with engineers on when to land certain features.

When new work comes up after a plan is established, ask “Why now?” Does the work you are about to add need to get done right away? If so, why?

If new work is emergent, that’s ok, what needs to be dropped from your current plan to pick up this work? It’s crucial to communicate relative priority of new work when adding it to the plan.

Reprioritization means committed deliverables in the future may shift. Check the effect of slotting in the new work on your current plan, and proactively push dates out and communicate them to your leaders.

Fixing what doesn’t need fixed

Not all events happen according to plan. Exceptions happen, when they do, it’s the manager’s job to deep dive and figure out whether anything is broken and fixing what needs fixed.

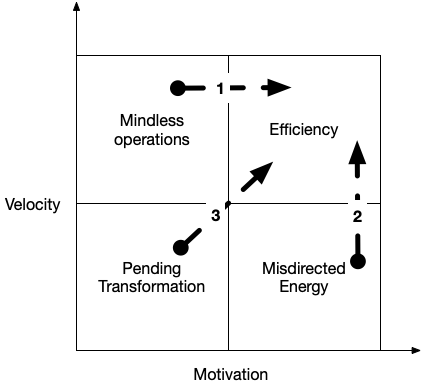

Figure 1 below illustrates an engineer’s output as a function of motivation and velocity, and managerial influence is the transformation. Ultimately, it’s a manager’s job to move everyone towards Efficiency, but more importantly is to identify which state is an engineer in, before acting.

Figure 1: Output = F (M, V), where M is motivation, V is velocity, and F is managerial influence

(1) Mindless Operations, a high-velocity engineer who loses motivation to work each day is a sign that the work isn’t interesting enough, or simply isn’t interesting enough for the engineer. The result of this is that the team output suffers. Sure, this team could close a lot of tickets, execute a lot of CMs (change management), but actual impactful projects keep getting delayed in favor of the next emergent issue. This could be caused by a “Day-2” mentality team, or a team that has too much tech debt and not enough attention to operational excellence, or the engineer has simply outgrown the current challenges they are presented with.

It’s up to the manager to sell and motivate the team, drum up morale, and make some hard decisions. Maybe it’s ok to drop OE for a week to work on high output long term initiatives, or maybe the team shouldn’t do what they are being asked to do day-in day-out, and instead reprioritize the roadmap to finish existing features before committing to building new features.

(2) Misdirected Energy is when highly motivated engineers work on the wrong tasks leading to slow velocity. This is what happened to Andy. To fix this, the manager needs to reflect on why we landed in this state, by answering these questions:

-

Have you set and communicated the correct priority? Are they blocked on something which you can fix?

-

Have you adequately equipped the engineer with the right tools?

-

Is there a problem with the engineer’s capabilities?

So long as there are no issues with the engineer’s capabilities it is always better for the manager to correct course and reflect on what the manager did wrong to cause the engineer to be in this state instead of asking inquisitive questions that are veiled accusations.

(3) I found the following mechanisms help boost a team’s bonding, motivation, and velocity in general.

-

Make sure people talk to each other, a good atmosphere is where no question is stupid, and anyone can feel open to speak their mind.

-

Sign people up for training, suggest conferences to go to, team travel is a great way to jolt conversation and inspire collaboration.

-

Periodic celebrations — could be anything, from a team member’s birthday to a feature launch party.

-

Have 1:1s, and ask “what have I made more confusing recently”